Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut came to the throne of Egypt in 1478 BC. Her rise to power was noteworthy as it required her to utilize her bloodline, education, and an understanding of religion. Her bloodline was impeccable as she was the daughter, sister, and wife of a king. Her understanding of religion allowed her to establish herself as the God's Wife of Amun Officially, she ruled jointly with Thutmose III, who had ascended to the throne the previous year as a child of about two years old. Hatshepsut was the chief wife of Thutmose II, Thutmose III's father. She is generally regarded by Egyptologists as one of the most successful pharaohs, reigning longer than any other woman of an indigenous Egyptian dynasty. According to Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, she is also known as "the first great woman in history of whom we are informed.

Hatshepsut was the daughter and only child of Thutmose I and his primary wife, Ahmose. Her husband Thutmose II was the son of Thutmose I and a secondary wife named Mutnofret, who carried the title King's daughter and was probably a child of Ahmose I. Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter named Neferure. After having their daughter, Hatshepsut could not bear any more children. Thutmose II with Iset, a secondary wife, would father Thutmose III, who would succeed Hatshepsut as pharaoh.

Reign

Trade with other countries was re-established; here trees transported by ship from Punt are shown being moved ashore for planting in Egypt—relief from Hatshepsut mortuary temple

Although contemporary records of her reign are documented in diverse ancient sources, Hatshepsut was thought by early modern scholars as only having served as a co-regent from about 1479 to 1458 BC, during years seven to twenty-one of the reign previously identified as that of Thutmose III , Today Egyptologists generally agree that Hatshepsut assumed the position of pharaoh.[12][13]

Hatshepsut was described as having a reign of about 21 years by ancient authors. Josephus and Julius Africanus both quote Manetho's king list, mentioning a woman called Amessis or Amensis who has been identified (from the context) as Hatshepsut. In Josephus' work, her reign is described as lasting 21 years and nine months,[14] while Africanus stated it was twenty-two years. At this point in the histories, records of the reign of Hatshepsut end, since the first major foreign campaign of Thutmose III was dated to his 22nd year, which also would have been Hatshepsut's 22nd year as pharaoh.

Dating the beginning of her reign is more difficult, however. Her father's reign began in either 1526 or 1506 BC according to the high and low estimates of her reign, respectively.[16] The length of the reigns of Thutmose I and Thutmose II, however, cannot be determined with absolute certainty. With short reigns, Hatshepsut would have ascended the throne 14 years after the coronation of Thutmose I, her father , Longer reigns would put her ascension 25 years after Thutmose I's coronation.[16] Thus, Hatshepsut could have assumed power as early as 1512 BC, or, as late as 1479 BC.

The earliest attestation of Hatshepsut as pharaoh occurs in the tomb of Ramose and Hatnofer, where a collection of grave goods contained a single pottery jar or amphora from the tomb's chamber—which was stamped with the date "Year 7".[18] Another jar from the same tomb—which was discovered in situ by a 1935–36 Metropolitan Museum of Art expedition on a hillside near Thebes — was stamped with the seal of the "God's Wife Hatshepsut" while two jars bore the seal of "The Good Goddess Maatkare , The dating of the amphorae, "sealed into the [tomb's] burial chamber by the debris from Senenmut's own tomb," is undisputed, which means that Hatshepsut was acknowledged as king, and not queen, of Egypt by Year 7 of her reign.

Major accomplishments

Trade routes

Hatshepsut re-established the trade networks that had been disrupted during the Hyksos occupation of Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, thereby building the wealth of the Eighteenth Dynasty. She oversaw the preparations and funding for a mission to the Land of Punt. This trading expedition to Punt was roughly during the ninth year of Hatshepsut's reign. It set out in her name with five ships, each measuring 70 feet (21 m) long, bearing several sails[dubious – discuss] and accommodating 210 men that included sailors and 30 rowers.[citation needed] Many trade goods were bought in Punt, notably frankincense and myrrh.

Hatshepsut's delegation returned from Punt bearing 31 live myrrh trees, the roots of which were carefully kept in baskets for the duration of the voyage. This was the first recorded attempt to transplant foreign trees. It is reported that Hatshepsut had these trees planted in the courts of her mortuary temple complex. Egyptians also returned with a number of other gifts from Punt, among which was frankincense , Hatshepsut would grind the charred frankincense into kohl eyeliner. This is the first recorded use of the resin.

Hatshepsut had the expedition commemorated in relief at Deir el-Bahari, which is also famous for its realistic depiction of the Queen of the Land of Punt, Queen Ati , The Puntite Queen is portrayed as relatively tall and her physique was generously proportioned, with large breasts and rolls of fat on her body. Due to the fat deposits on her buttocks, it has sometimes been argued that she may have had steatopygia. However, according to the pathologist Marc Armand Ruffer, the main characteristic of a steatopygous woman is a disproportion in size between the buttocks and thighs, which was not the case with Ati. She instead appears to have been generally obese, a condition that was exaggerated by excessive lordosis or curvature of the lower spine , Hatshepsut also sent raiding expeditions to Byblos and the Sinai Peninsula shortly after the Punt expedition. Very little is known about these expeditions. Although many Egyptologists have claimed that her foreign policy was mainly peaceful, it is possible that she led military campaigns against Nubia and Canaan.

Building projectsEdit

Djeser-Djeseru is the main building of Hatshepsut's mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahri. Designed by Senemut, her vizier, the building is an example of perfect symmetry that predates the Parthenon, and it was the first complex built on the site she chose, which would become the Valley of the Kings

Hatshepsut was one of the most prolific builders in ancient Egypt, commissioning hundreds of construction projects throughout both Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. Arguably, her buildings were grander and more numerous than those of any of her Middle Kingdom predecessors'. Later pharaohs attempted to claim some of her projects as theirs. She employed the great architect Ineni, who also had worked for her father, her husband, and for the royal steward Senemut. During her reign, so much statuary was produced that almost every major museum with Ancient Egyptian artifacts in the world has Hatshepsut statuary among their collections; for instance, the Hatshepsut Room in New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art is dedicated solely to some of these pieces.

Following the tradition of most pharaohs, Hatshepsut had monuments constructed at the Temple of Karnak. She also restored the original Precinct of Mut, the ancient great goddess of Egypt, at Karnak that had been ravaged by the foreign rulers during the Hyksos occupation. It later was ravaged by other pharaohs, who took one part after another to use in their own pet projects. The precinct awaits restoration. She had twin obelisks, at the time the tallest in the world, erected at the entrance to the temple. One still stands, as the tallest surviving ancient obelisk on Earth; the other has broken in two and toppled. The official in charge of those obelisks was the high steward Amenhotep.

Another project, Karnak's Red Chapel, or Chapelle Rouge, was intended as a barque shrine and originally may have stood between her two obelisks. It was lined with carved stones that depicted significant events in Hatshepsut's life.

Later, she ordered the construction of two more obelisks to celebrate her 16th year as pharaoh; one of the obelisks broke during construction and a third was therefore constructed to replace it. The broken obelisk was left at its quarrying site in Aswan, where it still remains. Known as the Unfinished Obelisk, it provides evidence of how obelisks were quarried.

Comparison with other female rulers

Although it was uncommon for Egypt to be ruled by a woman, the situation was not unprecedented. As a regant, Hatshepsut was preceded merneth of the first Dynasty, who was buried with the full honors of a pharaoh and may have ruled in her own right. Nimaathap of the thirds denasty may have been the dowadar of , but certainly acted as regent for her son, djoser, and may have reigned as pharaoh in her own right , nitcros may have been the last pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty. Her name is found in the histories of Herodotus and writings of maneths, but her historicity is uncertain. Queen Sobekneferu of the 12 denasty known to have assumed formal power as ruler of "Upper and Lower Egypt" three centuries earlier than Hatshepsut. Ahhotep I, lauded as a warrior queen, may have been a regent between the reigns of two of her sons, Kamose and Ahmose I, at the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty and the beginning of Hatshepsut's own Eighteenth Dynasty. Amenhotep I, also preceding Hatshepsut in the Eighteenth Dynasty, probably came to power while a young child and his mother, Ahmose-Nefertari, is thought to have been a regent for him.[30] Other women whose possible reigns as pharaohs are under study include Akhenaten's possible female co-regent/successor (usually identified as either Nefertiti or Meritaten) and Twosret. Among the later, non-indigenous Egyptian dynasties, the most notable example of another woman who became pharaoh was Cleopatra VII, the last pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. Perhaps in an effort to ease anxiety over the prospect of a female pharaoh, Hatshepsut claimed a divine right to rule based on the authority of the god amun

In comparison with other female pharaohs, Hatshepsut's reign was much longer and more prosperous. She was successful in warfare early in her reign, but generally is considered to be a pharaoh who inaugurated a long peaceful era. She re-established international trading and relationship lost during foreign occupation by the Hyksos and brought great wealth to Egypt. That wealth enabled Hatshepsut to initiate building projects that raised the calibre of Ancient Egyptian architecture to a standard, comparable to classical architecture, that would not be rivaled by any other culture for a thousand years. She managed to rule for more than 20 years. One of the most famous things that she did was build Hatshepsut's temple (see above).

Official lauding

Hyperope is common to virtually all royal inscriptions of Egyptian history. While all ancient leaders used it to laud their achievements, Hatshepsut has been called the most accomplished pharaoh at promoting her accomplishments This may have resulted from the extensive building executed during her time as pharaoh, in comparison with many others. It afforded her many opportunities to laud herself, but it also reflected the wealth that her policies and administration brought to Egypt, enabling her to finance such projects. Aggrandizement of their achievements was traditional when pharaohs built temples and their tombs.

Although it was uncommon for Egypt to be ruled by a woman, the situation was not unprecedented. As a regent, Hatshepsut was preceded by Merneith of the First Dynasty, who was buried with the full honors of a pharaoh and may have ruled in her own right. Nimaathap of the Third Dynasty may have been the dowager of Khasekhemwy, but certainly acted as regent for her son, Djoser, and may have reigned as pharaoh in her own right.[29] Nitocris may have been the last pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty. Her name is found in the Histories of Herodotus and writings of Manetho, but her historicity is uncertain. Queen Sobekneferu of the Twelfth Dynasty is known to have assumed formal power as ruler of "Upper and Lower Egypt" three centuries earlier than Hatshepsut. Ahhotep I, lauded as a warrior queen, may have been a regent between the reigns of two of her sons, Kamose and Ahmose I, at the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty and the beginning of Hatshepsut's own Eighteenth Dynasty. Amenhotep I, also preceding Hatshepsut in the Eighteenth Dynasty, probably came to power while a young child and his mother, Ahmose-Nefertari, is thought to have been a regent for him.[30] Other women whose possible reigns as pharaohs are under study include Akhenaten's possible female co-regent/successor (usually identified as either Nefertiti or Meritaten) and Twosret. Among the later, non-indigenous Egyptian dynasties, the most notable example of another woman who became pharaoh was Cleopatra VII, the last pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. Perhaps in an effort to ease anxiety over the prospect of a female pharaoh, Hatshepsut claimed a divine right to rule based on the authority of the god Amun.

In comparison with other female pharaohs, Hatshepsut's reign was much longer and more prosperous. She was successful in warfare early in her reign, but generally is considered to be a pharaoh who inaugurated a long peaceful era. She re-established international trading relationships lost during foreign occupation by the Hyksos and brought great wealth to Egypt. That wealth enabled Hatshepsut to initiate building projects that raised the calibre of Ancient Egyptian architecture to a standard, comparable to classical architecture, that would not be rivaled by any other culture for a thousand years. She managed to rule for more than 20 years. One of the most famous things that she did was build Hatshepsut's temple (see above).

Official lauding

See also: Depiction of Hatshepsut's birth and coronation

Hyperbole is common to virtually all royal inscriptions of Egyptian history. While all ancient leaders used it to laud their achievements, Hatshepsut has been called the most accomplished pharaoh at promoting her accomplishments.[32] This may have resulted from the extensive building executed during her time as pharaoh, in comparison with many others. It afforded her many opportunities to laud herself, but it also reflected the wealth that her policies and administration brought to Egypt, enabling her to finance such projects. Aggrandizement of their achievements was traditional when pharaohs built temples and their tombs.

Large granite sphinx bearing the likeness of the pharaoh Hatshepsut, depicted with the traditional false beard, a symbol of her pharaonic power—Metropolitan Museum of Art

Women had a relatively high status in ancient Egypt and enjoyed the legal right to own, inherit, or will property. A woman becoming pharaoh was rare, however; only Sobekneferu, Khentkaus I and possibly Nitocris preceded her.Nefernferuaten and Twosret may have been the only women to succeed her among the indigenous rulers. In Egyptian history, there was no word for a "queen regnant" as in contemporary history, "king" being the ancient Egyptian title regardless of gender, and by the time of her reign, pharaoh had become the name for the ruler. Hatshepsut is not unique, however, in taking the title of king. Sobekneferu, ruling six dynasties prior to Hatshepsut, also did so when she ruled Egypt. Hatshepsut had been well trained in her duties as the daughter of the pharaoh. During her father's reign she held the powerful office of God's Wife. She had taken a strong role as queen to her husband and was well experienced in the administration of her kingdom by the time she became pharaoh. There is no indication of challenges to her leadership and, until her death, her co-regent remained in a secondary role, quite amicably heading her powerful army—which would have given him the power necessary to overthrow a usurper of his rightful place, if that had been the case.

Hatshepsut assumed all of the regalia and symbols of the pharaonic office in official representations: the Khat head cloth, topped with the uraeus, the traditional false beard, and shendyt kilt.[32] Many existing statues alternatively show her in typically feminine attire as well as those that depict her in the royal ceremonial attire. Statues portraying Sobekneferu also combine elements of traditional male and female iconography and, by tradition, may have served as inspiration for these works commissioned by Hatshepsut.[34] After this period of transition ended, however, most formal depictions of Hatshepsut as pharaoh showed her in the royal attire, with all of the pharaonic regalia.

At her mortuary temple, in Osirian statues that regaled the transportation of the pharaoh to the world of the dead, the symbols of the pharaoh as the deity Osiris were the reason for the attire and they were much more important to be displayed traditionally; her breasts are obscured behind her crossed arms holding the royal staffs of the two kingdoms she ruled. This became a pointed concern among writers who sought reasons for the generic style of the shrouded statues and led to misinterpretations. Understanding of the religious symbolism was required to interpret the statues correctly. Interpretations by these early scholars varied and often, were baseless conjectures of their own contemporary values. The possible reasons for her breasts not being emphasized in the most formal statues were debated among some early Egyptologists, who failed to understand the ritual religious symbolism, to take into account the fact that many women and goddesses portrayed in ancient Egyptian art often lack delineation of breasts, and that the physical aspect of the gender of pharaohs was never stressed in the art. With few exceptions, subjects were idealized.

Changing recognition

Toward the end of the reign of tohotmoss III and into the reign of his son, an attempt was made to remove Hatshepsut from certain historical and pharaonic records — This elimination was carried out in the most literal way possible. Her cartouches and images were chiseled off some stone walls, leaving very obvious Hatshepsut-shaped gaps in the artwork.

At the Deir el-Bahari temple, Hatshepsut's numerous statues were torn down and in many cases, smashed or disfigured before being buried in a pit. At Karnak, there even was an attempt to wall up her obelisks. While it is clear that much of this rewriting of Hatshepsut's history occurred only during the close of Thutmose III's reign, it is not clear why it happened, other than the typical pattern of self-promotion that existed among the pharaohs and their administrators, or perhaps saving money by not building new monuments for the burial of Thutmose III and instead, using the grand structures built by Hatshepsut.

Amenhotep second the son of Thutmose III, who became a co-regent toward the end of his father's reign, is suspected by some as being the defacer during the end of the reign of a very old pharaoh. He would have had a motive because his position in the royal lineage was not so strong as to assure his elevation to pharaoh. He is documented, further, as having usurped many of Hatshepsut's accomplishments during his own reign. His reign is marked with attempts to break the royal lineage as well, not recording the names of his queens and eliminating the powerful titles and official roles of royal women, such as God's Wife of Amun.

For many years, presuming that it was Thutmose III acting out of resentment once he became pharaoh, early modern Egyptologists presumed that the erasures were similar to the Roman damnatio memoriae. This appeared to make sense when thinking that Thutmose might have been an unwilling co-regent for years. This assessment of the situation probably is too simplistic, however. It is highly unlikely that the determined and focused Thutmose—not only Egypt's most successful general, but an acclaimed athlete, author, historian, botanist, and architect—would have brooded for two decades of his own reign before attempting to avenge himself on his stepmother and aunt. According to renowned Egyptologist :

Here and there, in the dark recesses of a shrine or tomb where no plebeian eye could see, the queen's cartouche and figure were left intact ... which never vulgar eye would again behold, still conveyed for the king the warmth and awe of a divine presence.[51]

The erasures were sporadic and haphazard, with only the more visible and accessible images of Hatshepsut being removed; had it been more complete, we would not now have so many images of Hatshepsut. Thutmose III may have died before these changes were finished and it may be that he never intended a total obliteration of her memory. In fact, we have no evidence to support the assumption that Thutmose hated or resented Hatshepsut during her lifetime. Had that been true, as head of the army, in a position given to him by Hatshepsut (who was clearly not worried about her co-regent's loyalty), he surely could have led a successful coup, but he made no attempt to challenge her authority during her reign, and her accomplishments and images remained featured on all of the public buildings she built for twenty years after her death.

Tyldesley hypothesis

Joyce Tyldesley hypothesized that it is possible that Thutmose III, lacking any sinister motivation, may have decided toward the end of his life to relegate Hatshepsut to her expected place as the regent—which was the traditional role of powerful women in Egypt's court as the example of Queen Ahhotep attests—rather than pharaoh. Tyldesley fashions her concept as, that by eliminating the more obvious traces of Hatshepsut's monuments as pharaoh and reducing her status to that of his co-regent, Thutmose III could claim that the royal succession ran directly from Thutmose II to Thutmose III without any interference from his aunt.

The deliberate erasures or mutilations of the numerous public celebrations of her accomplishments, but not the rarely seen ones, would be all that was necessary to obscure Hatshepsut's accomplishments. Moreover, by the latter half of Thutmose III's reign, the more prominent high officials who had served Hatshepsut would have died, thereby eliminating the powerful religious and bureaucratic resistance to a change in direction in a highly stratified culture. Hatshepsut's highest official and closest supporter, Senenmut, seems either to have retired abruptly or died around Years 16 and 20 of Hatshepsut's reign, and was never interred in either of his carefully prepared tombs.According to Tyldesley, the enigma of Senenmut's sudden disappearance "teased Egyptologists for decades" given "the lack of solid archaeological or textual evidence" and permitted "the vivid imagination of Senenmut-scholars to run wild" resulting in a variety of strongly held solutions "some of which would do credit to any fictional murder/mystery plot. In such a scenario, newer court officials, appointed by Thutmose III, also would have had an interest in promoting the many achievements of their master in order to assure the continued success of their own families.

Presuming that it was Thutmose III (rather than his co-regent son), Tyldesley also put forth a about Thutmose suggesting that his erasures and defacement of Hatshepsut's monuments could have been a cold, but rational attempt on his part to extinguish the memory of an "unconventional female king whose reign might possibly be interpreted by future generations as a grave offence against , and whose unorthodox coregency" could "cast serious doubt upon the legitimacy of his own right to rule. Hatshepsut's crime need not be anything more than the fact that she was a woman.Tyldesley conjectured that Thutmose III may have considered the possibility that the example of a successful female king in Egyptian history could demonstrate that a woman was as capable at governing Egypt as a traditional male king, which could persuade "future generations of potentially strong female kings" to not "remain content with their traditional lot as wife, sister and eventual mother of a king" and assume the crown. Dismissing relatively recent history known to Thutmose III of another woman who was king, sobekan nerfa of Egypt's Middle Kingdom, she conjectured further that he might have thought that while she had enjoyed a short, approximately four-year reign, she ruled "at the very end of a fading [12th dynasty] Dynasty, and from the very start of her reign the odds had been stacked against her. She was, therefore, acceptable to conservative Egyptians as a patriotic 'Warrior Queen' who had failed" to rejuvenate Egypt's fortunes. In contrast, Hatshepsut's glorious reign was a completely different case: she demonstrated that women were as capable as men of ruling the two lands since she successfully presided over a prosperous Egypt for more than two decades. If Thutmose III's intent was to forestall the possibility of a woman assuming the throne, as proposed by Tyldesley, it was a failure since Twosret and Neferneferuaten (possibly), a female co-regent or successor of Akhenaten, assumed the throne for short reigns as pharaoh later in the nesw kingdoms.

Hatshepsut Problem

The erasure of Hatshepsut's name—whatever the reason or the person ordering it—almost caused her to disappear from Egypt's archaeological and written records. When nineteenth-century Egyptologists started to interpret the texts on the Deir el-Bahri temple walls (which were illustrated with two seemingly male kings) their translations made no sense. Jean-Francois campiglio, the French decoder of hierglephes, was not alone in feeling confused by the obvious conflict between words and pictures:

If I felt somewhat surprised at seeing here, as elsewhere throughout the temple, the renowned Moeris [Thutmose III], adorned with all the insignia of royalty, giving place to this Amenenthe [Hatshepsut], for whose name we may search the royal lists in vain, still more astonished was I to find upon reading the inscriptions that wherever they referred to this bearded king in the usual dress of the Pharaohs, nouns and verbs were in the feminine, as though a queen were in question. I found the same peculiarity everywhere...

The "Hatshepsut Problem" was a major issue in late 19th century and early 20th century Egyptology, centering on confusion and disagreement on the order of succession of early 18th denasty Egyptian kings. The dilemma takes its name from confusion over the chronology of the rule of Queen Hatshepsut and Thutmose I, II, and III. n its day, the problem was controversial enough to cause academic feuds between leading Egyptologists and created perceptions about the early Thutmosid family that persisted well into the 20th century, the influence of which still can be found in more recent works. Chronology-wise, the Hatshepsut problem was largely cleared up in the late 20th century, as more information about her and her reign was uncovered.

Archaeological discoveries

The 2006 discovery of a foundation despite including nine golden cartouche bearing the names of both Hatshepsut and Thutmose III in karnak may shed additional light on the eventual attempt by Thutmose III and his son Amenhotep II to erase Hatshepsut from the historical record and the correct nature of their relationships and her role as pharaoh.

Sphinx of Hatshepsut with unusual rounded ears and ruff that stress the lioness features of the statue, but with five toes – decorations from the lower ramp of her tomb complex. The statue incorporated the nemes headcloth and a royal beard; two defining characteristics of an Egyptian pharaoh. It was placed along with others in Hatshepsut's mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Thutmose III later on destroyed them but was resembled by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Date: 1479–1458 BC. Period: New Kingdom. 18th Dynasty. Medium: Granite, paint.

These two statues once resembled each other, however, the symbols of her pharaonic power: the double crown and traditional false beard have been stripped from the left image; many images portraying Hatshepsut were destroyed or vandalized within decades of her death, possibly by Amenhotep II at the end of the reign of Thutmose III, while he was his co-regent, in order to assure his own rise to pharaoh and then, to claim many of her accomplishments as his.

The image of Hatshepsut has been deliberately chipped away and removed – Ancient Egyptian wing of the royal Ontario museum

Dual stela of Hatshepsut (centre left) in the blue khepresh crown offering wine to the deity amun and Thutmose III behind her in the hedjet white crown, standing near worest – Vatican museum. Date: 1473–1458 BC. 18th Dynasty. Medium: Limestone.

This Relief Fragment Depicting Atum and Hatshepsut was uncovered in Lower Asasif, in the area of Hatshepsut's Valley Temple. It depicts the god Atum, one of Egypt's creator gods, at the left, investing Hatshepsut with royal regalia. Date: 1479–1458 BC. 18th Dynasty. Medium: Painted limestone.

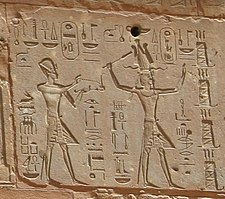

Hieroglyphs showing Thutmose III on the left and Hatshepsut on the right, she having the trappings of the greater role — Red Chapel, Karnak

A Fallen obelisk of Hatshepsut – Karnak.

Life-sized statue of Hatshepsut. She is shown wearing the nemes-headcloth and shendyt-kilt, which are both traditional for an Egyptian king. The statue is more feminine, given the body structure. Traces of blue pigments showed that the statue was originally painted. Date: 1479–1458 BC. Period: New Kingdom. 18th Dynasty. Medium: Indurated limestone, paint. Location: Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, Egypt.

A kneeling statue of Hatshepsut located at the central sanctuary in Deir el-Bahri dedicated to the god Amun-Re. The inscriptions on the statue showed that Hatshepsut is offering Amun-Re Maat, which translates to truth, order or justice. This shows that Hatshepsut is indicating that her reign is based on Maat. Date: 1479–1458 BC. Period: New Kingdom. 18th Dynasty. Medium: Granite. Location: Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, Egypt.

Left – Knot Amulet. Middle – Meskhetyu Instrument. Right – Ovoid Stone. On the knot amulet, Hatshepsut's name throne name, Maatkare, and her expanded name with Amun are inscribed. The Meskhetyu Instrument was used during a funerary ritual, Opening of the Mouth, to revive the deceased. On the Ovoid Stone, hieroglyphics was inscribed on it. The hieroglyphics translate to "The Good Goddess, Maatkare, she made [it] as her monument for her father, Amun-Re, at the stretching of the cord over Djeser-djeseru-Amun, which she did while alive." The stone may have been used as a hammering stone.

Kneeling figure of Queen Hatshepsut, from Western Thebes, Deir el-Bahari, Egypt, c. 1475 BC. Neues Museum

0 Comments